There's a lot of controversy about slavery in America and what Christians did about it. Skeptics point to Christians defending slavery in the 1800s, ignoring the fact that (1. Christ, as head of the Church, did not endorse slavery, (2. that many slaves--like Frederick Douglass and Samuel Ward--were Christians and (3. the anti-slavery movement was founded by Christians. This page is a repository of Christian anti-slavery literature.

A great resource for this subject is the Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection. There's also From Slavery to Freedom: The African-American Pamphlet Collection, 1822-1909, The Antislavery Literature Project and Records that pertain to American Slavery and the International Slave Trade from the National Archives.

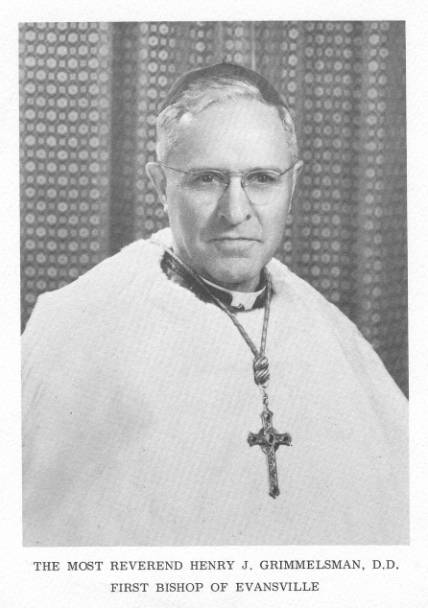

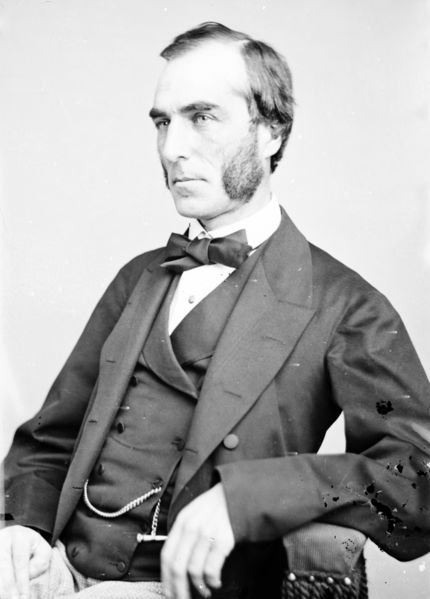

Congregationalist clergyman, educator. Senior editor of The Congregationalist (1849-1855), and an associate editor of the Christian Union from 1870. Read about Beecher here, here and here.

"Having thus tried to show the best side of slavery that I can conceive of, the reader can exercise his own judgment in deciding whether a man can be a Bible Christian, and yet hold his Christian brethren as property, so that they may be sold at any time in market, as sheep or oxen, to pay his debts.

"During my life in slavery I have been sold by professors of religion several times. In 1836 "Bro." Albert G. Sibley, of Bedford, Kentucky, sold me for $850 to "Bro." John Sibley; and in the same year he sold me to "Bro." Wm. Gatewood of Bedford, for $850. In 1839 "Bro." Gatewood sold me to Madison Garrison, a slave trader, of Louisville, Kentucky, with my wife and child--at a depreciated price because I was a runaway. In the same year he sold me with my family to "Bro." Whitfield, in the city of New Orleans, for $1200. in 1841 "Bro." Whitfield sold me from my family to Thomas Wilson and Co., blacklegs. In the same Tear they sold me to a "Bro." in the Indian Territory. I think he was a member of the Presbyterian Church. F. E. Whitfield was a deacon in regular standing in the Baptist Church. A. Sibley was a Methodist exhorter of the M. E. Church in good standing. J. Sibley was a class-leader in the same church; and Wm. Gatewood was also an acceptable member of the same church.

"Is this Christianity? Is it honest or right? Is it doing as we would be done by? Is it in accordance with the principles of humanity or justice?

"I believe slaveholding to be a sin against God and man under all circumstances. I have no sympathy with the person or persons who tolerate and support the system willingly and knowingly, morally, religiously or politically.

"Prayerfully and earnestly relying on the power of truth, and the aid of the divine providence, I trust that this little volume will bear some humble part in lighting up the path of freedom and revolutionizing public opinion upon this great subject. And I here pledge myself, God being my helper, ever to contend for the natural equality of the human family, without regard to color, which is but fading matter, while mind makes the man."

NEW YORK CITY, May 1, 1849.

-- pp. 203-204.

When I was about thirteen years old, and had succeeded in learning to read, every increase of knowledge, especially anything respecting the free states, was an additional weight to the almost intolerable burden of my thought--"I am a slave for life." To my bondage I could see no end. It was a terrible reality, and I shall never be able to tell how sadly that thought chafed my young spirit. Fortunately, or unfortunately, I had earned a little money in blacking boots for some gentlemen, with which I purchased of Mr. Knight, on Thames street, what was then a very popular school book, viz., "The Columbian Orator," for which I paid fifty cents. I was led to buy this book by hearing some little boys say they were going to learn some pieces out of it for the exhibition. This volume was indeed a rich treasure, and every opportunity afforded me, for a time, was spent in diligently perusing it. Among much other interesting matter, that which I read again and again with unflagging satisfaction was a short dialogue between a master and his slave. The slave is represented as having been recaptured in a second attempt to run away; and the master opens the dialogue with an upbraiding speech, charging the slave with ingratitude, and demanding to know what he has to say in his own defense. Thus upbraided and thus called upon to reply, the slave rejoins that he knows how little anything that he can say will avail, seeing that he is completely in the hands of his owner; and with noble resolution, calmly says, "I submit to my fate." Touched by the slave's answer, the master insists upon his further speaking, and recapitulates the many acts of kindness which he has performed toward the slave, and tells him he is permitted to speak for himself. Thus invited, the quondam slave made a spirited defense of himself, and thereafter the whole argument for and against slavery is brought out. The master was vanquished at every turn in the argument, and appreciating the fact he generously and meekly emancipates the slave, with his best wishes for his prosperity. It is unnecessary to say that a dialogue with such an origin and such an end, read by me when every nerve of my being was in revolt at my own condition as a slave, affected me most powerfully. I could not help feeling that the day might yet come, when the well-directed answers made by the slave to the master, in this instance, would find a counterpart in my own experience. This, however, was not all the fanaticism which I found in the Columbian Orator. I met there one of Sheridan's mighty speeches, on the subject of Catholic Emancipation, Lord Chatham's speech on the American War, and speeches by the great William Pitt, and by Fox. These were all choice documents to me, and I read them over and over again, with an interest ever increasing, because it was ever gaining in intelligence; for the more I read them the better I understood them. The reading of these speeches added much to my limited stock of language, and enabled me to give tongue to many interesting thoughts which had often flashed through my mind and died away for want of words in which to give them utterance. The mighty power and heart-searching directness of truth penetrating the heart of a slaveholder, compelling him to yield up his earthly interests to the claims of eternal justice, were finely illustrated in the dialogue, and from the speeches of Sheridan I got a bold and powerful denunciation of oppression and a most brilliant vindication of the rights of man. Here was indeed a noble acquisition. If I had ever wavered under the consideration that the Almighty, in some way, had ordained slavery and willed my enslavement for his own glory, I wavered no longer. I had now penetrated to the secret of all slavery and all oppression, and had ascertained their true foundation to be in the pride, the power, and the avarice of man. With a book in my hand so redolent of the principles of liberty, with a perception of my own human nature and the facts of my past and present experience, I was equal to a contest with the religious advocates of slavery, whether white or black, for blindness in this matter was not confined to the white people. I have met many good religious colored people at the south, who were under the delusion that God required them to submit to slavery and to wear their chains with meekness and humility. I could entertain no such nonsense as this, and I quite lost my patience when I found a colored man weak enough to believe such stuff.

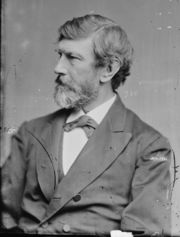

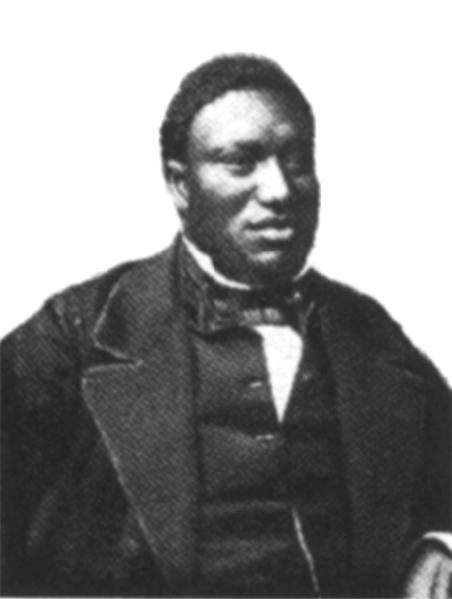

-- Frederick Douglass

"When, in 1787, the Constitution of the United States was adopted, there was but one opinion in the country on the subject of slavery, viz: that it was iniquitous and unprofitable; unjust to the slave, demoralizing to the master, inimical to free labor, and antagonistic to free institutions. No one thought of defending it, either from the Scriptures or on the ground of political economy. The slave States, especially, were weary of it, and lamented it as a heavy curse. It was the Old Man of the Sea whom they had innocently, or rather, unsuspectingly, taken on their shoulders and now could not shake off. The average price of able-bodied slaves was only from $250 to $300. But, in 1803, Louisiana was purchased, when the price of slaves went up to from $500 to $600, and some began to say, that possibly, after all, the institution might become profitable: but still the moral sentiment of the country was against it. With the acquisition of Florida in 1819, the price of slaves ran up to $800 and $1000, and slavery in the Southern States began to be regarded with decided favor; it was clearly profitable, and some Christian men were found who said, but timidly, it could be proved from the Scriptures that it was a divine institution. Then began in the North the anti-slavery agitation, that has been so misrepresented and abused, in opposition to the pro-slavery change of feelings and teachings in the South, and to bring back the sentiment of the country to what it was in the beginning -- the natural, or, if you will, unnatural father of abolitionism was slavery. But the leaven of iniquity continued to work. As new cotton, sugar and rice fields were opened, slaves increased in value and slavery became more and more profitable. In the older northern slave States, where slave labor was no longer profitable, it was profitable to breed slaves to sell to the more southern States. The average annual income to Virginia from this source, for more than a score of years preceding the rebellion, was from five to ten millions of dollars; one year, it is reported, running up as high as twenty millions. And as slaves increased in value, and slavery became increasingly profitable, the evidence increased in clearness that the institution was not only beneficent but divine. In 1845 Texas was annexed. The price of slaves went up to $1,500 and $2,000, audit became as clear as proofs from Holy Writ that the institution had the especial favor and protection of God, that to say aught against it was to be a 'troubler of Israel,' and that to be an abolitionist was to be an infidel.

"Thenceforward, for fifteen years, slavery ruled the country. It had but to ask, or rather demand, to receive. It had but to threaten, to be obeyed. Aye, it had but to signify its wish, to obtain. It subsidized the politics, the literature, the social customs, and, to a great extent, the religious and theological faith of the country. It was the one sacred thing that must not be doubted, under penalty of heresy and outlawry; and that must not be touched, except to caress and bless. When, O, when! since the birth of the Son of man, did any other enlightened Christian people humble themselves so abjectly before any other god so ugly and abominable! But, 'clear weather cometh out of the North.'"

"The tract, which evidences a self-taught knowledge of biblical Hebrew, examines a broad variety of primarily Old Testament verses to demonstrate differences between slavery as practiced among the ancient Hebrews and slavery in the American South. The author's purpose lies in proving to bible-cognizant readers that not only are the two systems incongruent, but that the terms of biblical slavery provide for eventual freedom. Therefore, the Southern system of perpetual slavery opposes the more liberal terms of slavery in the pastoral world of the Hebrew tribes. Buckingham measures the claim that the Bible authorizes slavery, which was a consistent theme of pro-slavery apologetic literature, against a social profile of slavery as it appeared in the Old Testament.

"Later in the text, Buckingham deals more briefly with the New Testament in order to juxtapose characteristic conditions of Southern slavery with cautionary New Testament verses. After his exegesis of biblical texts, he concludes "American slavery is enormously criminal, sinful in the pure light of the bible, and the way to get rid of it is clearly pointed out in that good book." (p. 22) An end to slavery is thus an end to catastrophic national sin that opposes divine commandments, a sin that can be remedied only with emancipation.

"Buckingham calls, among other points, for immediate emancipation of slaves; payment of fair wages for labor; establishment of marriage ceremonies and personal chastity among ex-slaves; and a religious mission to freed slaves to provide them with churches, schools, and ministers. Adopting an attitude common among both religious and secular whites, Buckingham viewed blacks as living within a "great darkness" (p. 22) that required moral reform and uplift from benevolent whites.

"This relatively brief text reflects the religious character of antislavery debate in Ohio, and through counter-example seeks to contradict the bible citations employed by pro-slavery advocates. It is the work of an obscure grassroots moral reform activist, determined to disprove any citation of the bible in support of slavery."

"Involuntary servitude was forbidden by the divine law, and the service appointed by the constitution of the Jewish state was a free [voluntary] service." p. 72.

"There was never, at any time, in the Jewish [Bible] statutes, or authorized by them, any such thing as slavery in the Hebrew nation; never any claim of property in man. When they fled out of Egypt, there were no slaves with them; the census of souls is that of free souls only; not a creature went out of Egypt on compulsion. And the laws promulgated by Moses, in regard to the obtaining and the treatment of servants, were in no respect what is called slave-legislation, but legislation against slavery;legislation to render its introduction into the nation absolutely and forever impossible; legislation only for the voluntary contracts of service with free men. The obtaining of a servant by such a contract was called the buying of him; it was simply and solely the buying of his time and service for such period as might be specified in the contract; and, to prevent the possibility of such service running into slavery by long possession, the period itself of such contracts was limited to six years; and if in any case extended to a longer time, only by solemn mutual agreement, and in no case, on no consideration, nor with any party, could such contract hold beyond the jubilee. Every fifty years, every servant in the land was free. And children were never servants because their parents were; no claim upon the time or service of the parents created any claim to that of the children. Servitude was not transmitted by birth, and never could be. Every instance of service, whether of the Hebrews or the heathen, was by free voluntary contract. The same phraseology is used of contracts with the heathen as of those with the Hebrews, and the one is no more a possession than the other." pp. 97-98.

"There never was such a thing as slavery among the Hebrews, nor ever any such thing as slave-legislation; they had no word in the language to signify a slave, nor did God ever permit any such word to be brought in; the heaventaught dialect refused to entertain it. The word always and from the outset employed for servant is from the very word used to describe the occupation of our father Adam in tilling the ground; and labor was never disgraceful, but always honorable, among the Hebrews. When they were about to be settled as a nation in Palestine, surrounded by heathen nations, that had among them the abominations of slavery, as of every other wickedness, in full blast, then, in preparation for such a settlement, and to guard against the temptation and the possibility of the introduction of slavery from abroad, it became necessary to prepare that body of jurisprudence, by which, in every respect, their policy was to be determined in regard to this fundamental matter in human society. And when it was perfected, it was not, and is not now, as many seem to imagine, legislation for the regulation or neutralization of slavery, as if any form of slavery had existed, or was permitted in their social system, but legislation absolutely and entirely against it, legislation in abhorrence of it, legislation condemning and forbidding it under penalty of death. From the first grand statute, HE THAT STEALETH A MAN, AND SELLETH HIM, OR IF HE BE FOUND IN HIS HAND, SHALL SURELY BE PUT TO DEATH, down to the minutest specifications of oppression, and the forms of imprecation against it, such as, "Cursed be he that useth his neighbor's service, and giveth him not for his hire,"' "Cursed be he that defraudeth the hireling in his wages,' these laws are a blaze of light against this mighty sin." pp. 203-203.

American clergyman and author. Read about Dexter here and here.

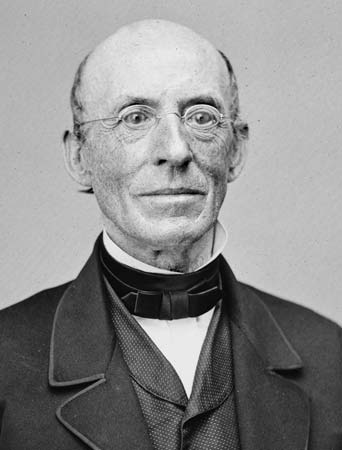

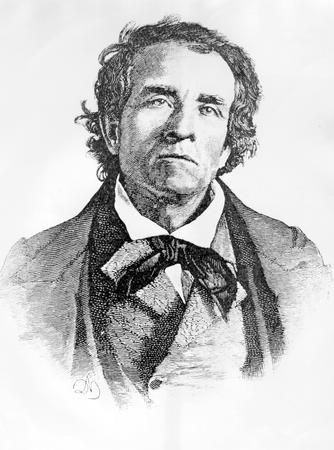

The question is sometimes asked, when, where and by whom the Negro was first suspected of having any rights at all? In answer to this inquiry it has been asserted that William Lloyd Garrison originated the Anti-slavery movement, that until his voice was raised against the American slave system, the whole world was silent. With all respect to those who make this claim I am compelled to dissent from it. I love and venerate the memory of William Lloyd Garrison. I knew him long and well. He was a grand man, a moral hero, a man whose acquaintance and friendship it was a great privilege to enjoy. While liberty has a friend on earth, and slavery an earnest enemy, his name and his works will be held in profound and grateful memory. To him it was given to formulate and thunder against oppression and slavery the testimonies of all ages. He revived, but did not originate.

It is no disparagement to him to affirm that he was preceded by many other good men whom it would it would be a pleasure to remember on occasions like this one. Benjamin Lundy, an humble Quaker, though not the originator of the Anti-slavery movement, was in advance of Mr. Garrison. Walker, a colored man, whose appeal against slavery startled the land like a trump of coming judgment, was before either Mr. Garrison or Mr. Lundy.

Emancipation, without delay, was preached by Dr. Hopkins, of Rhode Island, long before the voice of either Garrison, Lundy or Walker was heard in the land. John Wesley, a hundred years before, had denounced slavery as the sum of all villainies. Adam Clark had done the same. The Society of Friends had abolished slavery among themselves and had borne testimony against the evil, long before the modern Anti-slavery movement was inaugurated.

In fact, the rights of the Negro, as a man and a brother, began to be asserted with the earliest American Colonial history, and I derive hope from the fact, that the discussion still goes on, and the claims of the Negro rise higher and higher as the years roll by. Two hundred years of discussion has abated no jot of its power or its vitality. Behind it we have a great cloud of witnesses, going back to the beginning of our country and to the very foundation of our government. Our best men have given their voices and their votes on the right side of it, through all our generations.

It has been fashionable of late years to denounce it as a product of Northern growth, a Yankee device for disturbing and disrupting the bonds of the Union, and the like, but the facts of history are all the other way. The Anti-Slavery side of the discussion has a Southern rather than a Northern origin.

The first publication in assertion and vindication of any right of the Negro, of which I have any knowledge, was written more than two hundred years ago, by Rev. Morgan Godwin, a missionary of Virginia and Jamaica. This was only a plea for the right of the Negro to baptism and church membership. The last publication of any considerable note, of which I have any knowledge, is a recent article in the Popular Science Monthly, by Prof. Gilliam. The distance and difference between these two publications, in point of time, gives us a gauge by which we may in good degree measure the progress of the Negro. The book of Godwin was published in 1680, and the article of Gilliam was published in 1883. The space in time between the two is not greater than the space in morals and enlightenment. The ground taken in respect to the Negro, in the one, is low. The ground taken in respect to the possibilities of the Negro, in the other, is so high as to be somewhat startling, not only to the white man, but also to the black man himself.

... Here, to-night on the twenty-first anniversary of Emancipation in the District of Columbia, the capital of the grandest Republic of freedom on the earth, I kneel at the grave, amid the dust and shadows of bygone centuries, and offer my gratitude, and the gratitude of six millions of my race, to Morgan Godwin, as the grand pioneer of Garrison, Lundy, Goodell, Phillips, Henry Wilson, Gerrit Smith, Joshua R. Giddings, Abraham Lincoln, Thaddeus Stevens, and the illustrious host of great men who have since risen to plead the cause of the negro against those who would oppress him.

APPENDIX I find, since reading over the foregoing Narrative, that I have, in several instances, spoken in such a tone and manner, respecting religion, as may possibly lead those unacquainted with my religious views to suppose me an opponent of all religion. To remove the liability of such misapprehension, I deem it proper to append the following brief explanation. What I have said respecting and against religion, I mean strictly to apply to the _slaveholding religion_ of this land, and with no possible reference to Christianity proper; for, between the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference--so wide, that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked. To be the friend of the one, is of necessity to be the enemy of the other. I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land."

"I love the religion of our blessed Savior. I love that religion that comes from above, in the "wisdom of God, which is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, and easy to be entreated, full of mercy and good fruits, without partiality and without hypocrisy. I love that religion that sends its votaries to bind up the wounds of him that has fallen among thieves. I love that religion that makes it the duty of its disciples to visit the fatherless and the widow in their affliction. I love that religion that is based upon the glorious principle, of love to God and love to man; which makes its followers do unto others as they themselves would be done by. If you demand liberty to yourself, it says, grant it to your neighbors. If you claim a right to think for yourself, it says, allow your neighbors the same right. If you claim to act for yourself, it says, allow your neighbors the same right. It is because I love this religion' that I hate the slaveholding, the woman-whipping, the mind-darkening, the soul-destroying religion that exists in the southern states of America. It is because I regard the one as good, and pure, and holy, that I cannot but regard the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked. Loving the one I must hate the other; holding to the one I must reject the other." Page 416.

The frequent hearing of my mistress reading the Bible aloud, for she often read aloud when her husband was absent, awakened my curiosity in respect to this mystery of reading, and roused in me the desire to learn. Up to this time I had known nothing whatever of this wonderful art, and my ignorance and inexperience of what it could do for me, as well as my confidence in my mistress, emboldened me to ask her to teach me to read. With an unconsciousness and inexperience equal to my own, she readily consented, and in an incredibly short time, by her kind assistance, I had mastered the alphabet and could spell words of three or four letters. My mistress seemed almost as proud of my progress as if I had been her own child, and supposing that her husband would be as well pleased, she made no secret of what she was doing for me. Indeed, she exultingly told him of the aptness of her pupil, and of her intention to persevere in teaching me, as she felt her duty to do, at least to read the Bible. And here arose the first dark cloud over my Baltimore prospects, the precursor of chilling blasts and drenching storms. Master Hugh was astounded beyond measure, and probably for the first time proceeded to unfold to his wife the true philosophy of the slave system, and the peculiar rules necessary in the nature of the case to be observed in the management of human chattels. Of course he forbade her to give me any further instruction, telling her in the first place that to do so was unlawful, as it was also unsafe; "for," said he, "if you give a nigger an inch he will take an ell. Learning will spoil the best nigger in the world. If he learns to read the Bible it will forever unfit him to be a slave. He should know nothing but the will of his master, and learn to obey it. As to himself, learning will do him no good, but a great deal of harm, making him disconsolate and unhappy. If you teach him how to read, he'll want to know how to write, and this accomplished, he'll be running away with himself." Such was the tenor of Master Hugh's oracular exposition; and it must be confessed that he very clearly comprehended the nature and the requirements of the relation of master and slave. His discourse was the first decidedly anti-slavery lecture to which it had been my lot to listen.

... Previously to my contemplation of the anti-slavery movement and its probable results, my mind had been seriously awakened to the subject of religion. I was not more than thirteen years old, when in my loneliness and destitution I longed for some one to whom I could go, as to a father and protector. The preaching of a white Methodist minister, named Hanson, was the means of causing me to feel that in God I had such a friend. He thought that all men, great and small, bond and free, were sinners in the sight of God: that they were by nature rebels against his government; and that they must repent of their sins, and be reconciled to God through Christ. I cannot say that I had a very distinct notion of what was required of me, but one thing I did know well: I was wretched and had no means of making myself otherwise. I consulted a good colored man named Charles Lawson, and in tones of holy affection he told me to pray, and to "cast all my care upon God." This I sought to do; and though for weeks I was a poor, broken-hearted mourner, traveling through doubts and fears, I finally found my burden lightened, and my heart relieved. I loved all mankind, slaveholders not excepted, though I abhorred slavery more than ever. I saw the world in a new light, and my great concern was to have everybody converted. My desire to learn increased, and especially, did I want a thorough acquaintance with the contents of the Bible. I have gathered scattered pages of the Bible from the filthy street-gutters, and washed and dried them, that in moments of leisure I might get a word or two of wisdom from them. While thus religiously seeking knowledge, I became acquainted with a good old colored man named Lawson. This man not only prayed three times a day, but he prayed as he walked through the streets, at his work, on his dray--everywhere. His life was a life of prayer, and his words when he spoke to any one, were about a better world. Uncle Lawson lived near Master Hugh's house, and becoming deeply attached to him, I went often with him to prayer-meeting, and spent much of my leisure time with him on Sunday. The old man could read a little, and I was a great help to him in making out the hard words, for I was a better reader than he. I could teach him "the letter," but he could teach me "the spirit," and refreshing times we had together, in singing and praying. These meetings went on for a long time without the knowledge of Master Hugh or my mistress. Both knew, however, that I had become religious, and seemed to respect my conscientious piety. My mistress was still a professor of religion, and belonged to class. Her leader was no less a person than Rev. Beverly Waugh, the presiding elder, and afterwards one of the bishops of the Methodist Episcopal church.

In view of the cares and anxieties incident to the life she was leading, and especially in view of the separation from religious associations to which she was subjected, my mistress had, as I have before stated, become lukewarm, and needed to be looked up by her leader. This often brought Mr. Waugh to our house, and gave me an opportunity to hear him exhort and pray. But my chief instructor in religious matters was Uncle Lawson. He was my spiritual father and I loved him intensely, and was at his house every chance I could get. This pleasure, however, was not long unquestioned. Master Hugh became averse to our intimacy, and threatened to whip me if I ever went there again. I now felt myself persecuted by a wicked man, and I would go. The good old man had told me that the "Lord had a great work for me to do," and I must prepare to do it; that he had been shown that I must preach the gospel. His words made a very deep impression upon me, and I verily felt that some such work was before me, though I could not see how I could ever engage in its performance. "The good Lord would bring it to pass in his own good time," he said, and that I must go on reading and studying the scriptures. This advice and these suggestions were not without their influence on my character and destiny. He fanned my already intense love of knowledge into a flame by assuring me that I was to be a useful man in the world. When I would say to him, "How can these things be? and what can I do?" his simple reply, was, "Trust in the Lord." When I would tell him, "I am a slave, and a slave for life, how can I do anything?" he would quietly answer, "The Lord can make you free, my dear; all things are possible with Him; only have faith in God.'Ask, and it shall be given you.' If you want liberty, ask the Lord for it in FAITH, and he will give it to you."

Thus assured and thus cheered on under the inspiration of hope, I worked and prayed with a light heart, believing that my life was under the guidance of a wisdom higher than my own. With all other blessings sought at the mercy seat, I always prayed that God would, of his great mercy and in his own good time, deliver me from my bondage.

"It is no evidence that the Bible is a bad book, because those who profess to believe the Bible are bad. The slaveholders of the South, and many of their wicked allies at the North, claim the Bible for slavery; shall we, therefore, fling the Bible away as a pro-slavery book? It would be as reasonable to do so as it would be to fling away the Constitution."-- p. 45.

American classical scholar, Jay Professor of Greek Language and Literature, Columbia College. Of Drisler Encyclopedia Britannica notes, "He was ardently opposed to slavery, and brilliantly refuted The Bible View of Slavery, written by Bishop J. H. Hopkins of Vermont, in a Reply (1863), which meets the bishop on purely Biblical ground and displays the wide range of Dr. Drisler's scholarship."

"The same scripture (1 Cor. 6:10) which says drunkards shall not enter the kingdom of heaven, says also, No EXTORTIONER shall enter the kingdom of heaven. That slave-holding is the worst form of extortion, few will deny," p. 10.

"We have sometimes used the terms slave and slavery in the preceding discussion, but any one can see that the Mosaic servitude had none of the characteristics of modern slavery." p 17.

"The rights of the servant, then, were protected by awful penalties for their violation. Let such laws be now established as the civil law of the land, and slavery would be, like prowling beasts before the morning sun, hastening to caves of darkness and gloom. Now, if systems entirely dissimilar in every element should be represented by different words, then the term slavery should never be used to designate the servitude under the Mosaic economy." p. 63.

"The word slave is used but once in the New Testament, and then, not to translate --- but ---" (soma.) Rev. xviii.13. And those who would see in prospective the awful calamity of those who enslave, may turn to that chapter, and read the suffering of her, the smoke of whose torment ascendeth up for ever and ever." p. 76.

Attorney, minister, educator, soldier. 20th President of the United States. Read about President Garfield here, here and here.

The jurisdiction of this Constitution now covers an area fifty times greater than that of the original thirteen States and a population twenty times greater than that of 1780.

The supreme trial of the Constitution came at last under the tremendous pressure of civil war. We ourselves are witnesses that the Union emerged from the blood and fire of that conflict purified and made stronger for all the beneficent purposes of good government.

And now, at the close of this first century of growth, with the inspirations of its history in their hearts, our people have lately reviewed the condition of the nation, passed judgment upon the conduct and opinions of political parties, and have registered their will concerning the future administration of the Government. To interpret and to execute that will in accordance with the Constitution is the paramount duty of the Executive.

Even from this brief review it is manifest that the nation is resolutely facing to the front, resolved to employ its best energies in developing the great possibilities of the future. Sacredly preserving whatever has been gained to liberty and good government during the century, our people are determined to leave behind them all those bitter controversies concerning things which have been irrevocably settled, and the further discussion of which can only stir up strife and delay the onward march.

The supremacy of the nation and its laws should be no longer a subject of debate. That discussion, which for half a century threatened the existence of the Union, was closed at last in the high court of war by a decree from which there is no appeal--that the Constitution and the laws made in pursuance thereof are and shall continue to be the supreme law of the land, binding alike upon the States and the people. This decree does not disturb the autonomy of the States nor interfere with any of their necessary rights of local self-government, but it does fix and establish the permanent supremacy of the Union.

The will of the nation, speaking with the voice of battle and through the amended Constitution, has fulfilled the great promise of 1776 by proclaiming "liberty throughout the land to all the inhabitants thereof."

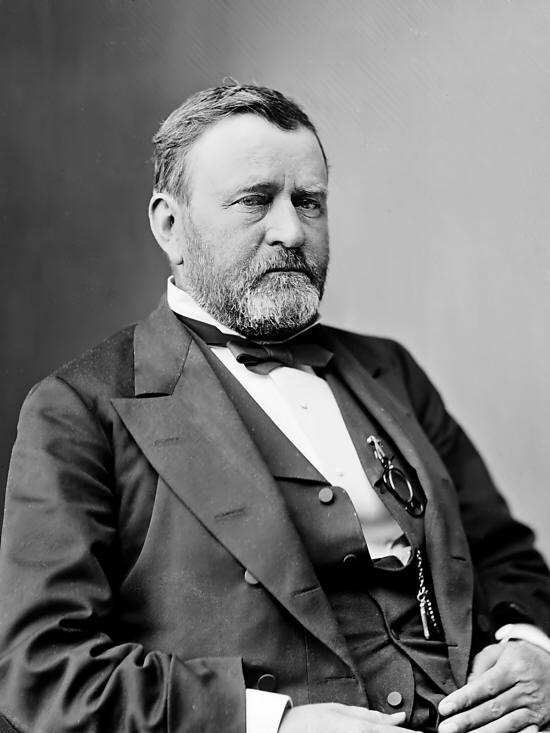

The elevation of the negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship is the most important political change we have known since the adoption of the Constitution of 1787. NO thoughtful man can fail to appreciate its beneficent effect upon our institutions and people. It has freed us from the perpetual danger of war and dissolution. It has added immensely to the moral and industrial forces of our people. It has liberated the master as well as the slave from a relation which wronged and enfeebled both. It has surrendered to their own guardianship the manhood of more than 5,000,000 people, and has opened to each one of them a career of freedom and usefulness. It has given new inspiration to the power of self-help in both races by making labor more honorable to the one and more necessary to the other. The influence of this force will grow greater and bear richer fruit with the coming years.

No doubt this great change has caused serious disturbance to our Southern communities. This is to be deplored, though it was perhaps unavoidable. But those who resisted the change should remember that under our institutions there was no middle ground for the negro race between slavery and equal citizenship. There can be no permanent disfranchised peasantry in the United States. Freedom can never yield its fullness of blessings so long as the law or its administration places the smallest obstacle in the pathway of any virtuous citizen.

The emancipated race has already made remarkable progress. With unquestioning devotion to the Union, with a patience and gentleness not born of fear, they have "followed the light as God gave them to see the light." They are rapidly laying the material foundations of self-support, widening their circle of intelligence, and beginning to enjoy the blessings that gather around the homes of the industrious poor. They deserve the generous encouragement of all good men. So far as my authority can lawfully extend they shall enjoy the full and equal protection of the Constitution and the laws.

There is much declamation about the sacredness of the compact which was formed between the free and slave states, on the adoption of the Constitution. A sacred compact, forsooth! We pronounce it the most bloody and heaven-daring arrangement ever made by men for the continuance and protection of a system of the most atrocious villany ever exhibited on earth. Yes--we recognize the compact, but with feelings of shame and indignation, and it will be held in everlasting infamy by the friends of justice and humanity throughout the world. It was a compact formed at the sacrifice of the bodies and souls of millions of our race, for the sake of achieving a political object--an unblushing and monstrous coalition to do evil that good might come. Such a compact was, in the nature of things and according to the law of God, null and void from the beginning. No body of men ever had the right to guarantee the holding of human beings in bondage. Who or what were the framers of our government, that they should dare confirm and authorise such high-handed villany--such flagrant robbery of the inalienable rights of man--such a glaring violation of all the precepts and injunctions of the gospel--such a savage war upon a sixth part of our whole population?--They were men, like ourselves--as fallible, as sinful, as weak, as ourselves. By the infamous bargain which they made between themselves, they virtually dethroned the Most High God, and trampled beneath their feet their own solemn and heaven-attested Declaration, that all men are created equal, and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights--among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. They had no lawful power to bind themselves, or their posterity, for one hour--for one moment--by such an unholy alliance. It was not valid then--it is not valid now.

Frederick Douglass, from Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: I had been living four or five months in New Bedford when there came a young man to me with a copy of the Liberator, the paper edited by William Lloyd Garrison, and published by Isaac Knapp, and asked me to subscribe for it. I told him I had but just escaped from slavery, and was of course very poor, and had no money then to pay for it. He was very willing to take me as a subscriber, notwithstanding, and from this time I was brought into contact with the mind of Mr. Garrison, and his paper took a place in my heart second only to the Bible. It detested slavery, and made no truce with the traffickers in the bodies and souls of men. It preached human brotherhood; it exposed hypocrisy and wickedness in high places; it denounced oppression, and with all the solemnity of "Thus saith the Lord," demanded the complete emancipation of my race. I loved this paper and its editor. He seemed to me an all-sufficient match to every opponent! whether they spoke in the name of the law or the gospel His words were full of holy fire, and straight to the point. Something of a hero-worshiper by nature, here was one to excite my admiration and reverence.

Soon after becoming a reader of the Liberator it was my privilege to listen to a lecture in Liberty Hall, by Mr. Garrison, its editor. He was then a young man, of a singularly pleasing countenance, and earnest and impressive manner. On this occasion he announced nearly all his heresies. His Bible was his text book--held sacred as the very word of the Eternal Father. He believed in sinless perfection, complete submission to insults and injuries, and literal obedience to the injunction if smitten "on one cheek to turn the other also." Not only was Sunday a Sabbath, but all days were Sabbaths, and to be kept holy. All sectarianism was false and mischievous-- the regenerated throughout the world being members of one body, and the head Christ Jesus. Prejudice against color was rebellion against God. Of all men beneath the sky, the slaves because most neglected and despised, were nearest and dearest to his great heart. Those ministers who defended slavery from the Bible were of their "father the devil"; and those churches which fellowshiped slaveholders as Christians, were synagogues of Satan, and our nation was a nation of liars. He was never loud and noisy, but calm and serene as a summer sky, and as pure. "You are the man-- the Moses, raised up by God, to deliver his modern Israel from bondage," was the spontaneous feeling of my heart, as I sat away back in the ball and listened to his mighty words,-- mighty in truth,--mighty in their simple earnestness. I had not long been a reader of the Liberator, and a listener to its editor, before I got a clear comprehension of the principles of the anti-slavery movement. I had already its spirit, and only needed to understand its principles and measures, and as I became acquainted with these my hope for the ultimate freedom of my race increased. Every week the Liberator came, and every week I made myself master of its contents. All the anti-slavery meetings held in New Bedford I promptly attended, my heart bounding at, every true utterance against the slave system, and every rebuke of it by its friends and supporters. Thus passed the first three years of my free life. I had not then dreamed of the possibility of my becoming a public advocate of the cause so deeply imbedded in my heart. It was enough for me to listen, to receive, and applaud the great words of others, and only whisper in private, among the white laborers on the wharves and elsewhere, the truths which burned in my heart.

"The ancient Romans had tested the policy of emancipation, to obtain soldiers in their wars against Hannibal. The testimony of Tiberius Gracchus, confirmed by Cicero, and approved by Montesquieu, assures us of the salutary effects. Christianity had abolished slavery throughout the Roman Empire without disaster." p. 370.

LETTER TO THE AUTHOR: “Uncle Tom's Cabin” is a gross exaggeration; that, of course, slavery is, after all, not so very bad; and that they, in doing its biddings, are not as base as they seem to be. You show them that the most educated and refined among the slaveholders have, for the past century, as legislators, been deliberately enacting the most fiendish of laws, in utter defiance of the moral sense of mankind, and the precepts of the blessed gospel of the Lord Jesus; and that their grave and learned judges have enforced these accursed statutes, in all their execrable rigor, thus giving a solemn sanction to the atrocities portrayed by Mrs. Stowe and others without number, still more aggravated by investing them with legal impunity. May God make your book a means of awakening the consciences of our cotton divines to the deep sin of upholding, in the name of the blessed and adorable Redeemer, a system so damnable as American Slavery! These reverend pro-slavery champions of Christianity resemble the priests of Juggernaut, recommending the worship of their god by pointing to the wretches writhing, and shrieking, and expiring under his car. That the blessing of God may rest on your labors for his glory and the good of our suffering and oppressed brethren, is the fervent prayer of

Your friend and servant,

WILLIAM JAY.

"If Thomas Jefferson doubted the superhuman origin of the Christian faith, he nevertheless did honor to its ethics. He acknowledged that he derived his first hint of a just government from the discipline of a Christian church, of the Baptist sect, in his neighborhood, whose polity was similar to that of the New England Puritans. It was by Thomas Jefferson, and in an atmosphere such as has been described, that the Declaration of Independence was written."

Reprinted in Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence; the best speeches delivered by the Negro from the days of slavery to the present time, edited by Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson. New York, The Bookery Publishing Company, c1914. New York: Johnson Reprint Corp., 1970. 512 pp. front. (port.) 23 cm.

16th American President. Read more about President Lincoln here and at The Library of Congress.

A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

"That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

"That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States." Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate-- we can not consecrate-- we can not hallow-- this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us-- that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion-- that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain-- that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom-- and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

This occasion would seem fitting for a lengthy response to the address which you have just made. I would make one, if prepared; but I am not. I would promise to respond in writing, had not experience taught me that business will not allow me to do so. I can only now say, as I have often before said, it has always been a sentiment with me that all mankind should be free. So far as able, within my sphere, I have always acted as I believed to be right and just; and I have done all I could for the good of mankind generally. In letters and documents sent from this office I have expressed myself better than I now can. In regard to this Great Book, I have but to say, it is the best gift God has given to man.

All the good the Saviour gave to the world was communicated through this book. But for it we could not know right from wrong. All things most desirable for man's welfare, here and hereafter, are to be found portrayed in it. To you I return my most sincere thanks for the very elegant copy of the great Book of God which you present.

"In the fall of 1996, the Illinois State Historical Library purchased the only extant copy of a handbill calling for an Illinois antislavery convention. The broadside, pictured above, announced the September 27, 1837, meeting of the state abolitionist group. Because it was signed by Elijah Lovejoy and undersigned by 245 persons from seventeen communities in ten counties of Illinois, the document represents the earliest comprehensive list of abolitionists in the state. Equally important is the fact that Elijah Lovejoy printed it in Alton shortly before his death at the hands of the anti-aboltionist mob in November of 1837."

State Convention: The Present aspect of the slavery question in this country, and especially in this State, is of commanding interest to us all. No question is, at the present time, exerting so strong an influence upon the public mind as this. The whole land is agitated by it. We cannot, nor would we remain indifferent spectators in the midst of developements so vitally interesting to us all, as those which are daily taking place in relation to the system of American slavery.

The undersigned would, therefore, respectfully call a meeting of the friends of the slave and of free discussion in the state of Illinois, to meet in Convention at Upper Alton, on the last Thursday of October. It is intended that this Convention should consist of all those in the state who believe that the system of American slavery is sinful and ought to be immediately abandoned, however diversified may be their views in other respects. It is desirable that the opponents in this state of domestic slavery--all who ardently long and pray to witness its immediate abolition, should co-operate together in their efforts to accomplish it. We therefore hope that all such will make it a point of duty to attend the Convention, not thereby feeling that they are pledged to any particular course of action, but that they may receive as well as impart the benefit of mutual counsel and advice.

It is earnestly to be hoped that there will be a full attendance at the Convention. Let all who feel deeply interested in this cause, not only attend themselves, but stir up their neighbors to attend also. And let each one remember that this call cannot be repeated. But for the destruction of the "Observer" press it would have been circulated some time since. It is hoped, that it will have time to circulate in season to bring together a large number of our friends from all parts of the state.

[List of abolitionists]

I hope in view of the fact, that the "Observer" press has been three times destroyed in Alton, in the space of little more than one year, it will not be deemed out of place, for me, in this special manner, to call upon the friends of law, of order, of equal rights, and of free discussion to rally at the proposed Convention in numbers and with a zeal corresponding to the urgency of the crisis. Our dearest rights are at stake--rights, which as American citizens ought to be dearer to us than our lives. Take away the right of Free discussion--the right under the laws, freely to utter and publish such sentiments as duty to God and the fulfilment of a good conscience may require, and we have nothing left to struggle for. Come up then, ye friends of God and man! come up to the rescue, and let it be known whether the spirit of freedom yet presides over the destinies of Illinois, or whether the "dark spirit of slavery has so far already diffused itself through our community, as that the discussion of the inalienable rights of man can no longer be tolerated.

ELIJAH P. LOVEJOY.

Alton, September 27, 1837.

... "After quoting all that the Old Testament says expressly on the subject of slavery, he turns to the New; and brings forth what Christ and his apostles have to do or not to do, with it. And all this part of his political pamphlet is so shocking to every principle of charity and good-will to men, that it needs special refutation. A sophomore, in his first College essay, might make this refutation easily, and even then do himself no great credit. And will it be believed by sensible men that Bishop Hopkins puts in capital letters as a most important and unanswerable proposition, our Lord's entire silence on the subject of slavery as a justification of it! And yet he does this very thing with an air of complete self-satisfaction and triumph. Hear him: "We ask what the Divine Redeemer said in reference to slavery. And the answer is perfectly undeniable: He did not allude to it at all." (p. 4.) What of it? Is silence always to be construed into assent? And can silence be fairly and always justly interpreted as meaning assent and justification? Not at all. Our Lord says nothing at all about the Jewish Sabbath passing over into the Christian Sunday; but is that any reason why He approved or disapproved of the change? He says nothing at all about suicide; but is that any reason why He approved and justified it? He says nothing at all about polygamy, although He speaks of marriage; but is that any reason why He sanctioned it? The words, Sunday, suicide and polygamy, are not once reported as ever having fallen from His lips; and yet the principles of His blessed religion are sufficiently explicit as to the things themselves. Upon what principle of interpretation, then, does Bishop Hopkins affirm that our Lord's silence on the subject of slavery in the Roman Empire, which by the way was not wholly African slavery, can be construed into its justification, any more than His silence on the matters of a change in the Jewish Sabbath, suicide and polygamy, can be construed for or against them? Silence here is a poor argument in favor of slavery, and the Bishop is certainly very ingenious, but not so ingenuous in making it serve his purpose. The Christian religion is but the full completion and development of the Jewish, and its abiding principles are one and the same throughout. All Revelation is a unit, showing us our duties to God and man. This Revelation was made complete and final in Jesus Christ and by Him; and therefore the Christian religion must be consistent with God's original revelations in Eden, and under the Patriarchal and Mosaic systems. It is designed to restore man's lost innocence and happiness, and is meant for the whole race, and for no particular part of it." p. 8.

... I have, for many years, seen on the face of the Constitution power to abolish every part of American slavery. But, formerly, I did not claim, that this power should be exercised to its full extent. One of the pro-slavery speculations on the intentions of the Constitution is, that the Federal Government was not to demand the abolition of slavery in the "old thirteen States." In common with most abolitionists, I deferred to this speculation, and left the slavery of those States to their own disposal. Now, however, for a considerable length of time, I have turned my back on all such speculations; and have been in favor of taking the Constitution just as it reads. Taking it just as it reads, we, of course, come, promptly, to the conclusion, that it enjoins the abolition of every part of American slavery. And, why should we not take it, just as it reads? Whence, indeed, our permission to take it otherwise? Most emphatically, whence our permission to do so, for the purpose of making out a case against the most essential and sacred human rights?

The following view of the Hebrew laws of slavery is compiled from Barnes' work on slavery, and from Professor Stowe's manuscript lectures.

The legislation commenced by making the great and common source of slavery--kidnapping--a capital crime.

The enactment is as follows: "He that stealeth a man and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death." Exodus xxi. 16.

The sources from which slaves were to be obtained were thus reduced to two: first, the voluntary sale of an individual by himself, which certainly does not come under the designation of involuntary servitude; second, the appropriation of captives taken in war, and the buying from the heathen.

With regard to the servitude of the Hebrew by a voluntary sale of himself, such servitude, by the statute-law of the land, came to an end once in seven years; so that the worst that could be made of it was that it was a voluntary contract to labour for a certain time.

With regard to the servants bought of the heathen, or of foreigners in the land, there was a statute by which their servitude was annulled once in fifty years.

It has been supposed, from a disconnected view of one particular passage in the Mosaic code, that God directly countenanced the treating of a slave, who was a stranger and foreigner, with more rigour and severity than a Hebrew slave. That this was not the case will appear from the following enactments which have express reference to strangers:

Thou shalt neither vex a stranger nor oppress him; for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt. Exodus xxii.21.

Thou shalt not oppress a stranger, for ye know the heart of a stramger. Exodus xxiii.9

The Lord your God regardeth not persons. He doth execute the judgment of the fatherless and the widow, and loveth the stranger in giving him food and raiment; love ye therefore the stranger. Deut. x.17-19.

Judge righteously between every man and his brother and the stranger that is with him. Deut. i.16.

Cursed be he that perverteth the judgment of the stranger. Deut. xxvii.19.

Boston clergyman. Slavery abolitionist.

"We expect, generally, that the progress of Christianity in a country will certainly, however gradually, undermine and overthrow customs and usages, superstitions and prejudices, of an unchristian character. That this contempt of the Negro is unchristian, perhaps I shall be excused from stooping to argue. But, alas! pari passu with the spread of what the pulpit renders current as Christianity in my native country, is the growth, diffusion, and perpetuity of hatred to the Negro; indeed, one might be almost tempted to accredit the words of one of the most eloquent of Englishmen, who, more than twenty years ago, described it in few but forcible terms--"the Negro-hating Christianity." Religion, however, should be substituted for Christianity; for while a religion may be from man, and a religion from such an origin may be capable of hating, Christianity is always from God, and, like him, is love. "He who hateth his brother abideth in darkness." "Love is the fulfilling of the law." p. 41.

"Some deny the sinfulness of slaveholding; others shelter themselves behind the faults of the abolitionists; others defend slaveholding from the Bible; but I think their love of harmony is their chief alleged reason for their present attitude. Let it not be forgotten, however, that behind all this--and going very far, I think, to explain it--is the contempt they all alike maintain towards the Negro. Surely, if they believed him to be an equal brother man, such miserable pretexts for, and defences of, the doing of the mightiest wrongs against him, would never for a moment be thought of." p. 67.

"I was most gratified to find that, among Dissenters as in the Establishment, simple faith in Christ's salvation is the great theme of the pulpit. Rev. J. Sherman I heard first; afterward, Rev. John Angell James, Rev. H. J. Bevis, Rev. Dr. Halley, Rev. Dr. Raffles, Rev. J. Baldwin Brown, Rev. Dr. Alexander, Rev. S. Bergne, the Hon. and Rev. Baptist Wriothesley Noel, Rev. Henry Allon, Rev. Samuel Martin, and Rev. C. H. Spurgeon. Varied in style, talent, learning, and other peculiarities, as are these gentlemen, and different as are the classes of their hearers, they all agree in preaching Jesus and his cross, for the redemption of a sinful world. Thus the Christian Churches in Great Britain are one in the maintenance and promulgation of that truth which saves; they are one in their love of the simple gospel, and in bringing forth the fruits of that gospel in their lives. Thus, for all practical purposes, the section of the Establishment to which I refer, and the Dissenting denominations, 'walk together,' because 'agreed.'

"Coming from a distant colony, as I do, and knowing how powerful is the Christian Church of this great country in moulding the religious character of the colonies--knowing, too, how much the colonies have to do with the evangelization of the heathen*

"If I am suspected of forgetting the very lamentable neglect of religion by too many, of all classes, in these islands, I have to say, that I do not forget, but recollect it vividly, as it stands forth in forms and illustrations most painfully abundant, everywhere. What I rejoice to know is, that God, in his infinite mercy, has been pleased to grant to his people here the power and the privilege of seeing the evils that are around them, and of holding and wielding the "spiritual weapons" which, being "mighty through God," fully enable them to "demolish the strongholds of Satan." I know not of a brighter, more hopeful, evidence of God's gracious favour to his modem Israel, than the earnest, simple love of the gospel--than its being sought for, preached, believed, felt, and honoured, by all departments and branches of the British Church. Long may this greatest of blessings be vouchsafed to them! Long may we of the colonies be blest with the benefits flowing from it! Widely may it extend, and may it yield fruits most abundant to the praise and glory of the Great Head of the Church! " pp. 410-412.

Lecture by Peter Williams from Lanier Theological Library on Vimeo.

Whether Ricardo Cardwell is a Christian is currently and publicly unknown, his comments about America's response to slavery are salient. Breitbart News posted this video on July 11, 2018: